December 30, 2019

Mistletoe Ranges Are Changing; So Are Recommendations On What To Do About It

Question:

There’s mixed advice out there on how to control mistletoe. What do you recommend?

- Question submitted via Sandoval County Extension Agent Lynda Garvin

Answer:

For me, the control approach depends mainly on the kind of tree, how bad the infestation is, and if the mistletoe is reasonably reachable. In a nutshell: there are many species of mistletoe (over 1,500 worldwide) and, for the most part, each one is species-specific. That is, mistletoe on your juniper will never infect your cottonwood tree or vice versa. This is yet another in a long list of reasons that support diversifying landscape species in our gardens!

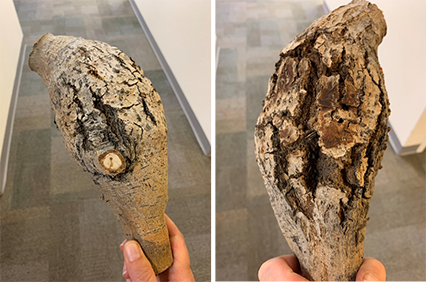

In a column about mistletoe last year, I explained that instead of roots, mistletoe develops root-like structures called haustoria that work themselves down past the bark and into the branches where they tap into vascular tissues to steal water and nutrients. This is why many people recommend removing mistletoe by cutting off actual tree branches to try to get as much of the infection out as possible. I’m afraid that when tree lovers try to prune out the mistletoe by cutting the tree limb they may be causing more harm than good. Remember, every pruning cut affects the entire tree and the larger the cut, the more damage.

Consider the level of infestation before taking action in your yard. Besides the injury from large pruning cuts, it may be impossible to remove all of the haustoria hidden in the trunk, especially in trees that have been infested for a long time. If the branch is swollen at the base of the mistletoe, there is a good chance the haustoria are already in the vascular tissue of the host plant and it will be much harder to remove all of the parasite. And you'll need to keep watch in the coming years to see if it grows back from that spot or another spot nearby.

I chatted with my predecessor, Dr. Curtis Smith, about this over coffee last month. He agreed that the damage from pruning may be worse than the damage caused by the mistletoe itself. Often, mistletoe is blamed for tree decline when really the trees were already aging and dying. Still, keeping infestations under control can help prevent further spreading to the same tree species nearby. We are both concerned that a broadleaf mistletoe that infects cottonwoods appears to be spreading further north along the Rio Grande each year. Although some species, like juniper mistletoe (Phoradendron juniperinum) and piñon dwarf mistletoe (Arceuthobium divaricatum), have always been around.

I learned all kinds of mistletoe tips and factoids when researching for this week’s column.

- Like pistachio trees, junipers, mulberry trees, and most cannabis plants, mistletoes are dioecious. Male flowers (producing pollen) and female flowers (producing berries with seeds) are borne on two different plants. You may not need to worry about seed dispersal if you have a male mistletoe plant. Although, male mistletoe plants can infect female mistletoe plants, so it’s not all cut and dried.

- The origin of the term “mistletoe” is not well defined, but may come from the German words “mist” (dung) and “tang” (branch) and be loosely translated as “poop on a stick.”

- Mistletoe seeds are coated with a natural “glue,” termed viscin that helps them stay in the tree long enough to infect the bark with their haustoria.

- A wide variety of birds feed on the berries of mistletoe, so it may provide important winter forage.

- While the whole plant, perhaps especially the berries, are considered toxic on some levels, medical research continues to explore the pharmaceutical capabilities of this strange plant.

- Juniper mistletoe (Phoradendron juniperinum) is one of our native mistletoes and was recently featured on the informative and interactive Native Plants of New Mexico Facebook page as the “Native Plant of the Week.”

- Recent research suggests that mistletoe could be a keystone species in native forest ecosystems and some believe that finding native mistletoe in native trees should be considered a good thing because it could be proof of a healthy, diverse ecosystem and not a threat at all!

If you’re surprised by any of these statements and want to learn more, check out the blog version of this column for source links galore.

Go out and take a look at the trees in your yard. If you see new mistletoe sprouting up on small limbs (smaller diameter than your thumb and therefore prunable with loppers) that are reachable from the ground or using a pole saw, consider making a clean cut several inches below the visible site of mistletoe attachment. For tips on pruning dos and don’ts, visit Desert Blooms and search “pruning.” If it’s too far up to reach safely, practice your lasso skills and see if you can knock off the mistletoe cluster without further injuring the tree or yourself. Either way, get a friend to record the adventure and tag @NMDesertBlooms when your video goes viral.

Marisa Y. Thompson, PhD, is the Extension Horticulture Specialist, in the Department of Extension Plant Sciences at the New Mexico State University Los Lunas Agricultural Science Center, email: desertblooms@nmsu.edu, office: 505-865-7340, ext. 113.

Links:

For more gardening information, visit the NMSU Extension Horticulture page at Desert Blooms and the NMSU Horticulture Publications page.

Send gardening questions to Southwest Yard and Garden - Attn: Dr. Marisa Thompson at desertblooms@nmsu.edu, or at the Desert Blooms Facebook page.

Please copy your County Extension Agent and indicate your county of residence when you submit your question!