April 28, 2018

Grape Girdling for Sweetness Is Different than Tree Girdling for Demise

Question:

Why is girdling discouraged in tree care but encouraged in grape growing?

- Barry F., Las Cruces, NM

Answer:

The difference between girdling in grapes versus trees is both subtle and crucially important. We’ve all seen tree rings before at some point, so let’s start there and take a field trip into the wood of the plant.

The more rings, the older the tree. The outermost ring, representing the most recent growth, is comprised of layers of tissue, each with a completely different purpose. Imagine for a minute a generic tree with a thin, gummy layer of tissue just underneath

the bark that hugs all of the trunk and every branch and root, new and old. This is the cambial tissue layer (or “cambium”), and it is responsible for the trunk and branches getting thicker each year because this is the zone where new cells are generated. Like a fruit rollup, this cambial layer is tender and juicy and can easily be damaged. (New cells are also made at the growing tips of branches and roots, but right now we’re focusing on the trunk girth and the fruit rollup. Stay with me.)

When cells on the outer part of the fruit rollup layer mature, they become inner bark (phloem) tissue that transports the tree’s food downward toward the roots. This food (aka “sugars,” “photosynthates,” “carbohydrates,” “energy-containing substances”) is formed mainly in the green, leafy tissues during photosynthesis. Can you imagine already how damage to this inner bark layer (phloem) disrupts the movement of the plant’s food?

Immediately inside the thin fruit rollup layer is another layer of tissue (xylem) that carries water and nutrients upward from the roots to the leaves and fruits. Further inside the trunk, those older rings represent older xylem tissue that may be still carrying water upward, but over time it becomes lignified heartwood, stops carrying water, and acts as structural support as the tree continues to grow.

Tree girdling is usually accidental, but can be deadly, regardless of intent. When the tree trunk is damaged either by actual cutting (like from weed whacker twine or lawnmower hits), picking off the outer bark pieces (big no-no because it protects layers underneath), or an old piece of wire that got imbedded as the tree trunk increased in circumference (see archived column on staking errors), those layers of tissue (phloem, cambium, and xylem) are potentially compromised. If the damage occurs all the way around the trunk, it is called girdling. Animals like rabbits, deer, or beetles can also girdle trees.

If the damage is very shallow, and the fruit rollup layer of cambial tissue is still intact, a new layer of inner bark (phloem) might be possible. If the fruit rollup is ruined all the way around, the tree will die because it can’t generate new growth. If the xylem layer is restricted all the way around, the tree will die faster because it can’t transport water and nutrients where they are needed.

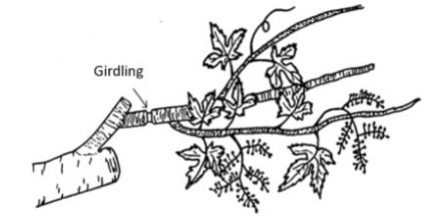

Girdling in grapes is a technique that involves removing of a thin ring of inner bark (phloem tissue) on a woody stem (cane), but the key is that the cambial and xylem layers are left intact. As NMSU Extension Viticulture Specialist Dr. Gill Giese explained in last week’s column, when the phloem is girdled, the sugars created in the leaves cannot move down toward the roots, so they have to stay up near the fruit and can result in sweeter, bigger grapes. Visit Desert Blooms for photos of girdling in grapes versus trees and links to more information. Share this column on social media and mention @NMDesertBlooms for a chance to win a grape-flavored fruit rollup.

Marisa Y. Thompson, PhD, is the Extension Horticulture Specialist, in the Department of Extension Plant Sciences at the New Mexico State University Los Lunas Agricultural Science Center, email: desertblooms@nmsu.edu, office: 505-865-7340, ext. 113.

Links:

For more gardening information, visit the NMSU Extension Horticulture page at Desert Blooms and the NMSU Horticulture Publications page.

Send gardening questions to Southwest Yard and Garden - Attn: Dr. Marisa Thompson at desertblooms@nmsu.edu, or at the Desert Blooms Facebook page.

Please copy your County Extension Agent and indicate your county of residence when you submit your question!